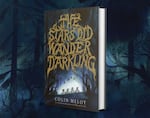

Colin Meloy's latest novel for middle grade readers, "The Stars did Wander Darkling," is set in a fictional Oregon town in 1987.

vc.nayak

Colin Meloy is perhaps best known as the songwriter and lead singer of The Decemberists, but he also writes books aimed at young readers. He authored the “Wildwood” series, which is now being made into a feature film, and he’s just come out with a new book, “The Stars did Wander Darkling.” It’s set in 1987 in an Oregon coastal town that draws inspiration from Astoria and Manzanita. Meloy also weaves poetry into the narrative, including Arthur Rimbaud, Lord Byron and William Butler Yeats, and he hopes to pique kids’ interest to read further. He joins us to talk more about the themes in the book and what he hopes middle-grade readers take away from it.

Note: The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. Colin Meloy is perhaps best known, especially to people, say, over the age of 25, as a songwriter and lead singer of the band The Decemberists. But for more than a decade now, he has also written books especially aimed at younger readers. He started with the “Wildwood” series which the Portland animation studio Laika is turning into a feature film. And he recently came out with a new book. It is a horror story set in a fictional town on the Oregon coast in 1987. It’s called “The Stars Did Wander Darkling.” Colin Meloy welcome back to Think Out Loud.

Colin Meloy: Thanks for having me.

Miller: I’m gonna do my best not to do any spoilers because this is the kind of book where I think that could hurt the reading experience. But so for people who haven’t read the book, can you just give us a sense for the basic premise?

Meloy: It is set in a fictional coastal Oregon town in 1987, a town called Seaham. It focuses around the adventures of a kid named Archie Coomes and his three closest friends, as a crack or a cave in a cliff on the coast has been broken open by Archie’s dad, who’s a construction contractor. He’s building a hotel up there on the headlands and in their work they’ve uncovered this crack in the cliff which has exposed this kind of darkness inside. And Archie and his friends go and check it out. One of the kids has a very strong vision-like reaction to what’s inside. Then it proceeds from there.

Miller: What attracted you to the coast? “The Wildwood Chronicles” were centered in a version of Portland and a very fanciful version of Forest Park. You went an hour and a half west?

Meloy: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think I’ve always loved books that use existing geography and kind of remap them because I think it kind of gives a sort of extra level of realism to it, that this is somehow accessible and yet is still in the realm of imagination and fiction. What attracted me to the coast, when I was 12, I grew up in Helena, Montana, very landlocked. In 1986, my grandparents moved to a house in Ashland and we all drove down to visit them and we drove down the coast. And the first time I’d ever seen the Oregon coast, a kid coming from Montana, it was just extraordinary. I think I’d been to Southern California beaches, but never that . . .

Miller: Never the overgrown . . .the version of the coast that is Oregon.

Meloy: The drama . . . which is unlike anywhere else. And I was 12. I was just a blooming short story writer myself, like kind of lost in my own head a lot and I think seeing the craggy cliffs and the windswept dunes and the windblown trees and all these things, the sort of staple dramatic elements of the coast, really captivated my imagination. Not only my proximity to the coast and my relationship to it now, I think was part of my setting the book there and then, but I think also trying to tap into my experience as a 12-year old, seeing that environment for the first time.

Miller: You mentioned words that to me, absolutely, I would use to describe the coast now: dramatic and overgrown. But can you think back, I mean did the 12-year old you also see a scariness or creepiness present there?

Meloy: Absolutely. I mean that’s part of it. I think that’s the drama, but I also was a horror obsessed 12-year old. I was really into horror, all sorts of genres, sci-fi and fantasy, but at that point, [I] was really in my sort of Stephen King mode. And I think part of the mist coming in and any of these old kind of weather-beaten houses, it really stokes your imagination. It also happened to be the summer that “The Goonies” had come out, and like a lot of people of our generation, that hit me like I was a gooney, those were my friends. That was me. And so I really identified with it.

Miller: As an outsider? As someone who people didn’t totally understand?

Meloy: Yeah. I think that’s it. Growing up in a small town feeling kind of iconoclastic was just feeling separate, a little bit ‘other’ from the typical kids in my school and I think my set of friends were similar in that way.

Miller: And I’m glad you mentioned that because there seemed to be some inescapable homages to “The Goonies” in this new book. I mean it’s a very different book, but there are some aspects where there’s overlap.

Meloy: Yeah, well I think it owes a lot to that sense of adventure. I think all middle grade books should have an element of “The Goonies” to it because the thing about “The Goonies” that I think is so attractive to kids is that those kids have agency, right? Those kids have to work beyond their parents and have to do things for themselves, and there’s a certain amount of independence and agency that you don’t necessarily have in real life that you can see modeled in “The Goonies.” I also think that was that time. I don’t think it’s really that far off the mark because growing up in Helena, a small town in the 80′s, we were left to our own devices so much of the time. And we were expected to provide our own transportation. We biked and then just got home in time for dinner.

Miller: I’m curious [about] adults in this new book. There’s one exception, and he’s the guy who runs the video rental store. So we could talk about his store. But besides him, the adults in this book are either useless, or worse, or verging on smarmy or just plain evil. Maybe because that’s where they are or something’s happened to them. I mean, this is a horror story, but that seems like you’re tapping into something, which is the way a lot of your readers view adults anyway, even outside of horror.

Meloy: Well, yeah, it is a horror story. But first and foremost, it’s a middle grade novel.

Miller: What are the ages for middle grade? It seems like it’s a publishing term?

Meloy: It is a publishing term and I maybe use it too much. But there’s picture books for younger kids. And there’s chapter books for very early readers. And then middle grade is like the 8 to 12 year old set. And then once you move beyond 8 to 12, you work into YA, young adult. And middle grade is what I’ve written, that set 8 to 12. For whatever reason, it always has attracted me, because I feel like you’re freer. You’re certainly freer than when you’re writing picture books or chapter books because you don’t have to keep in mind their reading level so much and really hand hold and be very careful about content and things like that.

With YA there’s also a certain expectation, and I don’t want to slight any YA writers or readers or anything, but often I think you might as well read an adult novel. I mean, unless it’s really speaking to a teen experience, ideally a YA novel would do that. Middle grade is like . . . that’s not like my 12 year old self on the Oregon coast for the first time. You have a foot in childhood, but you have a foot in adulthood. So there’s the ability to read and experience and process stuff that’s not necessarily a younger kid wouldn’t, and yet you’re still really steeped in that sort of imaginative world as well. There’s so much possibility.

Miller: But you said that in 1986 when you went to the coast for the first time, you were 12 and you were in your Stephen King phase. And I loved Stephen King. I feel like he taught me how to read novels for better or for worse and at times when there was all kinds of stuff that probably wasn’t, or I should say, definitely wasn’t appropriate for an 11 year old which was probably part of the thrill?

Meloy: Yeah.

Miller: What did Stephen King mean to you?

Meloy: And that’s another reason why I wanted to write this book. I reflected as a reader myself. Once I had moved beyond chapter books and even middle grade books, I was a pretty avid reader as a kid. And it was moving into middle school, there wasn’t really anything that grabbed me.. I had kind of moved beyond the Lloyd Alexander’s. the John Bellairs, and the Roald Dahls. We think of quintessential writers for that age group and just needed something. And I think a lot of kids and people in my generation have the same experience. We moved from those books because there wasn’t really anything else. There wasn’t a really rich middle grader or YA scene that was kind of dealing with the things that those kids really wanted, scarier stuff or, I don’t know, more gripping stuff. Anyway, I think leapt directly into Stephen King and V. C. Andrews and these kinds of adult books, but for us, our next step of reading from middle grade.

Miller: How do you decide though how scary to make a book like this? Because I should say that there were scenes where it doesn’t really feel like you’re pulling punches. Bad things happen that are described with clarity. I guess I could put it that way. What is too scary and what’s just scary enough as you’re imagining a 10-year old or a 12-year old?

Meloy: I feel like I didn’t want to underestimate the capacity of a 10-year old, 11-year old, a 12-year old to deal with these things.

Miller: Why not?

Meloy: Because I think that they want them. There’s an appetite to be genuinely scared and when I say genuinely scared, not scared and they’re like well it’s a Scooby doo. Well it turns out it was the guy all along. You know, it was the grocer, whoever, or Bunnicula or something like that. When I was starting to research for the book, just seeing what other scary novels for this age set were out there and they were all couched in ‘well this isn’t really real, this is funny or this is a mystery.’ And I know from myself as a kid and also having kids myself, there is a real desire to be genuinely scared. But then I thought also, like you, reflecting on my reading Stephen King, there’s a ton of stuff that’s like a bit much for a 12-year old. And I’m not saying scary stuff. I think the scary stuff was great. But more of the interpersonal things, a lot of adult stuff. I think particularly Stephen King tends to write damaged alcoholic male characters. There’s a lot of misogyny, abuse, like heavy stuff in there that maybe take that out, leave the scary stuff in and you’ve got a great book for a 12-year old.

Miller: I mentioned the video store owner, who is the one redeeming adult in the book. But there’s some fun scenes in his video store itself. It’s a kind of clubhouse for your characters, a place where young characters feel safe. What did video stores mean to you growing up?

Meloy: They meant a lot. In my hometown, there was actually a video store called National Video. I think that’s what it was called. That was beta only.

Miller: Well you should explain. So this is part of the plot early on, not an important part of the plot, but it’s a point. So many people may not know what betamax means, right?

Meloy: In the early days of taped video content, there were two warring formats. One was VHS and one was betamax. I mean they’re both tape, right, but one of them was kind of smaller and nobody knew which one would eventually win out. Of course VHS did and then became obsolete very quickly.

Miller: Even though it [VHS] was lower quality, which all the video nerds were right about. But it didn’t matter because the market had taken over?

Meloy: And I don’t know why VHS won over. But in any case, I think that led a lot of video store owners probably to make a decision. They carried both VHS and betamax, two copies of each movie or they just picked their side. And in Helena, somebody had done that and it was just betamax. And I feel like that was earlier, in like ‘84. But I like the idea that even in ‘87, when VHS had definitely kind of won that format war, he was still insistent on being a beta only store.

Miller: It’s a kind of a particular embrace of nerdom in this. I mean did you see yourself in that way and it’s funny to talk about now because there’s been such a reclamation of the term in some ways. I think people use that now to talk about coolness in a way. Being a nerd was not cool in the 1980′s.

Meloy: No, it wasn’t. That really has changed. Randy’s store, Movie Mayhem, which is kind of a shout out to Movie Madness by the way, a local Portland rental store. Anyway, it was a clubhouse. I wanted it to be an archetypal thing, right? Like the kids, the protagonists should have a place that is their own, that is a safe space, where they can work through their issues and then, their problem, decide on a plan and go out into the world and enact it. And then also I found that there’s a really powerful archetype in stories and in sci-fi, horror movies of the kind of sage figure or the guy who forges the sword.

Miller: A kind of Obi Wan Kenobi person?

Meloy: Yeah. And I thought that would be so great for the owner of the video store to be that person. So he is kind of arming them with knowledge as they try to figure out what’s going on in their town. He is using the knowledge that he’s gleaned from these movies and trying to teach them the ways of horror.

Miller: I want to see if we can talk briefly about some of the bad stuff that happens without getting to why it happens or what happens in the end. Because it’s a really creepy idea, it’s not a new idea of the people around you maybe not being quite what they seem, changing somehow and acting like it’s still your mom or your dad or the grocer or whoever. But maybe there’s something that’s happened to them. Why do you think this horror idea has such enduring appeal?

Meloy: I think particularly for kids, it touches into that fear of powerlessness, that the people in charge are not only checked out, they’re actually working against you. And that’s a fear that we have as adults, but particularly as kids. We’re relying so much on the adult world to protect us and to guide us. But I also think that that’s an important part of writing for kids as well and I’ve done that in all the other books. The adults do tend to be kind of checked out. I feel like Roald Dahl does such a fantastic job of that.

Miller: That’s the best case scenario for an adult in a Roald Dahl book, that they’re checked out, and they’re just as likely to eat you.

Meloy: You’re right. And I think that that’s really fascinating because that gives kids who are reading that an opportunity to not only imagine this authority figure in a completely different light, but then also it just places so much agency on them, they have independence, they have power. In a situation where they often feel very powerless as a kid. And in “The Stars Did Wander Darkling,” that’s a little bit darker because many of the adults end up kind of turning sort of evil. So it just kind of adds an extra layer of horror on top of that; that feeling of being under the thumb of the authoritative figures.

Miller: We talked about some of the 1980′s or after pop cultural references that you’ve threaded here or that you’re paying homage to. But even the name of the book implies that there’s another level of language that you’re using, including bits of poetry. What do you want your young readers to take away in terms of the poetry that you’re sprinkling here and there?

Meloy: I think for a couple of reasons: one I love putting that kind of stuff in there, that’s a little bit extra credit. You can easily read and understand it in context and it creates a kind of an environment or just a world that the book lives inside of. But if you want to go the extra step, you can be like, ‘What are these poems? I want to check out what the whole poem is or who wrote it.’

Miller: Extra credit. That’s the language of an 11th grade English teacher.

Meloy: I know. That’s a bad way to say it, but just like another layer. And I appreciated that. I feel like I’ve learned so much from books that . . . let me punch above my weight a little bit at my own end, on my own time. And then maybe even later, when they come across Lord Byron or Rimbaud in an English class, and be like, ‘Oh, I remember that from that book I read when I was a kid’. That aside, I think that’s secondary. It really is that the poems themselves and the language and the poems. It has to do with these three kind of beings that appear at the beginning of the book that are I think of as kind of gestating pieces of evil that are slowly becoming human and having to learn the ways of humanity and they do that by taking in their surroundings and making notes of it and discovering pieces of poetry as a way of human communication.

And also, at the time that I was writing this, I was reading a biography of Lord Byron and was reminded of so much of the romantic poetry; there’s some really scary stuff in it. It’s obviously like that, a lot of horror comes from the romantic movement when you think of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein coming out of that scene. And Lord Byron dipped his toe in that as well.

Miller: The book ends. There is a conclusion, but there are a lot of obvious areas of where the narrative could pick up again. Did you write this with a sequel in mind?

Meloy: You know, I didn’t. I think initially I thought that there were other stories to tell in this world and I still do. But I didn’t write the ending with the idea that it was a jumping off point for a sequel. I liked the idea of making an ending that was puzzling. I appreciate that in a book, you come to the end and there’s still work to be done. And there’s work to be done for you, the reader, in your imagination. And maybe that involves just kind of thinking it through and imagining moving on. Sometimes it involves going back through and reading other sections and I think it just gives you an opportunity to just go deeper into the book when things don’t get so sewn up in the end.

Miller: What are you reading right now that’s either scaring you or giving you joy, or maybe that’s the same thing?

Meloy: Gosh, well I did a bunch of horror reading as I was writing this, going back and reading a lot of those old Stephen King books.

Miller: What was that like?

Meloy: It was really interesting.

Miller: Books that you had read 30 years ago?

Meloy: I reread “It” and “Pet Cemetery” and “Carrie.” It was really interesting. It was kind of shocking, like, oh I’m imagining my 11-year old self, 10-year old self coming across some of these very adult situations. But I wasn’t too perturbed by it at the time. I took it all in stride. Yeah, what have I been reading? Gosh, Sylvia Townsend Warner was a contemporary of T.H. White that I’ve kind of gotten into recently. But as far as scary stuff, I think I read a lot prepping for this and kind of moved on for a little while.

Miller: Colin Meloy, it was a pleasure talking to you.

Meloy: Oh, yeah. Thanks for having me.

Miller: That’s Colin Meloy. The lead singer and songwriter of The Decemberists, the author of a number of books for young readers, including “The Wildwood Chronicles” and his new novel. It’s called “The Stars Did Wander Darkling.”

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.