Don Allen III got a text that struck him with dread. “Looks like a fire rippin’ maybe a couple miles east of Gold Butte,” it read. Then a follow up text: “According to Coffin it’s further north.”

Cryptic to most people, Allen knew exactly what the two texts meant and what was at stake. They had been sent from a fire lookout tower on Sand Mountain, a peak in the Willamette National Forest near Three Finger Jack and Mount Washington. Allen knew the lookout tower well. He’d lived there when his dad worked as a lookout, and he had helped rebuild the tower 30 years ago after it had been destroyed by fire.

To the north was the Coffin Mountain Lookout where Allen had first worked as a lookout. The ranger on duty could see exactly what Allen feared: a plume of smoke broiling from the south flank of Mount Hood.

Allen immediately texted back, “I hope not too close to Bull of the Woods.”

On a high peak in the middle of the Bull of the Woods Wilderness area stood the Bull of the Woods Lookout. Built in 1942, it was one of the oldest and most iconic historic lookout towers in the Northwest, and one of the very last. Allen’s father had worked at The Bull of the Woods Lookout when he was a young man. It shaped his father’s life, and his. Now, a massive wildfire was growing somewhere in its vicinity.

Allen and the Sand Mountain Society, a volunteer nonprofit dedicated to preserving the last of the Northwest’s historic lookout towers, had been waiting to resume their restoration work on the lookout tower for more than 15 years and had finally gotten permission to return.

Since the spring, Allen had been preparing to return to the Bull of the Woods Lookout with his father and the Sand Mountain crew for a multiday work session over Labor Day weekend.

Suddenly, those plans were on hold as the Bull Complex Fire grew, moving closer to the lookout tower. Fire had threatened the tower in the past and it had survived. If wildland fire crews could reach it in time and wrap it with a fire-resistant covering, it might have a chance. If not, Oregon would lose one of its great historic treasures. For Allen, it would feel like the undoing of his life’s work and the end of a family legacy.

Bull Complex Fire approaching the Bull of the Woods Lookout, the day before it burned down.

US Forest Service

Three generations of lookouts

Allen’s connection to fire lookout towers goes back three generations.

His grandfather had been one of the early Forest Service rangers of the 1920s and ‘30s dispatched to remote outposts to keep watch over the vast public forest reserves of the Northwest.

The lookouts were the first-line defense for spotting and reporting forest fires.

There were few roads penetrating the forests, and supplies had to be hauled up to the lookouts by pack animals. “The packer might be the only person you saw that summer,” Allen said. “It was a solitary life.”

Allen’s grandfather spoke fondly of his summer seasons in a lookout. The stories he recounted of life in the wilderness captured the imagination of his son, Don Allen Jr.

After graduating from high school in 1959, Allen Jr. followed his father’s footsteps and got his first job as a fire lookout. He was stationed at Bull of the Woods Lookout.

The young man found that life at a lookout tower suited him. When his lookout season ended in the fall, he started college at the University of Oregon, but returned to the Bull of the Woods Lookout for the next two summer seasons.

After his junior year, he moved to the Vinegar Hill Lookout in the Malheur National Forest. He was joined by his new wife, who was pregnant with their son, Don Allen III.

“I like to say my first time in a lookout was in the womb,” Allen jokes.

Allen’s earliest memories were formed at lookouts, particularly one atop a unique volcanic cinder cone formation in the Willamette National Forest called Sand Mountain.

The family lived at the Sand Mountain Lookout for three summer seasons. During their final year, the 1967 Big Lake Airstrip Fire threatened the lookout, forcing Allen, his mother and baby sister to be airlifted out, while his father stayed on duty.

The lookout survived the wildfire, only to be burned it down the following season by an accidental fire started by the lookout’s stove.

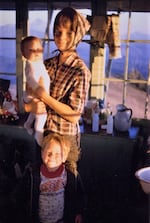

Don Allen with his mother and sister at Sand Mountain in 1966.

Don Allen Jr

Legend of the Bull

Just as his grandfather had told stories of his youthful years as a lookout, Allen’s father told stories of his time working in the Bull of the Woods Lookout, nicknamed “the Bull” for short.

“I always thought of the Bull of the Woods Lookout as legendary,” Allen said. “He made it sound like such a great adventure to be way up in a lookout on top of a mountain ridge, all alone in the middle of the wilderness.”

When Allen reached the age that his father had started his lookout career, his dad took him to see the Bull.

“I had tried to visualize it all my life, but when I saw it in person, I understood,” Allen said. “All of my dad’s stories I’d heard as a kid came together.”

At the Bull, the sense of remoteness felt palpable to Allen. “The more the feeling settles in, it lets you feel that feeling of real solitude,” Allen said. “Some people might find that scary. I found it comforting.”

When he was 21, Allen got his first job as a lookout, stationed at Coffin Mountain Lookout in the Willamette National Forest.

From his tower, Allen could see the lookout where his dad had gotten his start, Bull of the Woods; turning toward the south, he could look back at where his story with lookouts had started, Sand Mountain.

Standing on the catwalk of the Bull of the Woods Lookout, overlooking the Mt. Hood National Forest, 1956.

US Forest Service

The Sand Mountain Society

After fire destroyed the Sand Mountain Lookout in 1968, dozens of square miles of formerly dense forest became an open playground for off-road recreation. When he was 10, Allen saw a particularly rowdy group of dirt bikers aggressively cutting tracks in the cinderash soil. Allen felt angry, but helpless to stop them. After the group rode away, Allen picked up a scrap of lumber and used it to try to put the soil back as it had been.

In 1987, management plans for the Sand Mountain came up for review. Allen saw an opportunity to protect the fragile ecological area. Age 24 at the time, Allen founded the Sand Mountain Society. Working in cooperation with the Forest Service, the Sand Mountain Geologic Special Interest Area was formed. The new designation prohibited off-road recreation.

However, the new restriction was not warmly welcomed. Signs were ripped out and road barriers winched aside, Allen recalls.

Allen realized that Sand Mountain needed someone to keep an eye on things. But if anyone was going to stay on site consistently, they’d need a shelter. The future of Sand Mountain was in its past, Allen concluded. Sand Mountain needed its lookout tower back.

East Zigzag Lookout being burned by a Forest Service ranger in 1965. Many of the historic lookout towers were intentionally burned by the Forest Service.

US Forest Service

Lookout tower transplant

The use of lookout towers had been waning since Allen’s childhood. By the 1980s, many lookouts had been abandoned. Many fell victim to vandalism, or left to be slowly battered by weather to the point of collapse. Seeing the inventory of aging lookouts as a liability, Forest Service districts across the Northwest decommissioned most of the lookout towers by the fastest, most cost-effective means possible: burning them down.

Rather than simply build a new lookout tower on Sand Mountain, Allen and the band of volunteers (many of them former lookout rangers or retired Forest Service archaeologists) wanted the lookout to have historic integrity.

They went in search of a lookout of the same age, style and materials as the original Sand Mountain lookout. They found a match in the Rogue River National Forest.

When the Sand Mountain Society volunteers arrived at Whisky Peak in 1989, the lookout had been vacant for about 15 years and was likely facing a decommission by fire.

The Sand Mountain Society dismantled it board by board, and relocated it on Sand Mountain.

In the process, they discovered what would become the Sand Mountain Society modus operandi: salvage vintage pieces from historic buildings slated for destruction and repurpose the materials to repair the handful of lookouts that had the chance of being saved for posterity.

They completed the lookout at Sand Mountain in 1990, then started their next rescue mission.

The first project of the Sand Mountain Society.

Jan Zarella

Return to the Bull — false start

For the next dozen years, the Sand Mountain Society stayed busy, painstakingly pulling pieces from doomed structures to use in their restoration projects. Their list of successful projects grew slowly and steadily.

There was one lookout they especially wanted to restore — the Bull of the Woods Lookout.

“It needed some work,” Allen recalled, “but at the core it was sound.”

In 2005, Allen and his father hiked back to the Bull. With them was a string of pack mules hauling in building materials and a team of Sand Mountain Society volunteers carrying hand tools.

“Because it was in designated wilderness, we couldn’t use power tools,” Allen explained. “For us, it brought us back to what it was like in the old times, when the lookout was first built.”

The crew carefully pulled out 10 of the windows and strapped them onto pack mules to take back to the city for detailed restoration. They ripped out the old roof, and installed a temporary one. They painted the exterior to seal it from the weather, and battened down the lookout for the winter.

Planning to resume the work the following summer, they left their tools and bundles of cedar roof shingles.

Little did they know that administrative permission would delay their return, putting the restoration of Bull of the Woods on hold for the next 16 years.

The Bull of the Woods Lookout was one of the most iconic historic lookouts in the Northwest, looking over this vista toward Mount Hood for nearly 80 years.

US Forest Service

The Bull Complex Fire

When last spring arrived, Allen was excited. He had lined up a series of summer projects for the Sand Mountain Society volunteers, culminating with a big work session over Labor Day weekend. At long last, he’d gotten the go-ahead to return to Bull of the Woods.

As they prepared for their return, the summer grew increasingly hot and dry, spiking several days above 100, and setting historic records.

On Aug. 2, lightning struck the Bull of the Woods Wilderness, igniting the dry forest in several locations. The individual fires soon spread, creating the Bull Complex Fire.

Fire crews were rallied and fire management plans quickly drawn up. Within the discussions, the Forest Service Heritage Resource team identified key historic structures to focus protective efforts.

They reached out to Sand Mountain Society and reassured them that the Bull of the Woods Lookout was on that list.

The plan was to dispatch small crews to wrap the structures in fire-resistant material and to clear away the perimeter of trees and brush. This had been done to the Bull of the Woods Lookout during the 2011 Motherload Fire.

A mission was set up to fly a crew to the lookout on Aug. 14, but called off due to conditions. The team mobilized the next day, but conditions were still deemed unsafe.

Fire managers turned their efforts to wrapping other significant historic sites. Fire crews wrapped the buildings and bridges at Bagby Hot Springs, Hawk Mountain Lookout Cabin and the Gold Butte Lookout, which the Sand Mountain Society had restored.

Fire managers waited for an opportunity to dispatch a crew to wrap the Bull of the Woods Lookout.

Members of the Sand Mountain Society checked the updates on the fire incident maps, growing increasingly anxious as they watched fire advance toward the lookout. They sent a flurry of emails, offering to help and imploring the Forest Service to make every possible effort to save the historic lookout.

By the final week of August, the fire was within a half-mile of the lookout. It was clear that favorable weather conditions and personnel availability were not going to align in time to send a crew to wrap the lookout tower.

Fire managers launched a new tactic. For six days, helicopters dropped water in an attempt to slow the fire’s march toward the tower.

On the last day of August, a helicopter flew to the site, where a rappelling fire crew cleared trees and brush around the lookout.

By Labor Day weekend, the smoke engulfed the lookout. Burning embers rained down on the lookout’s uncovered roof.

Allen continued exchanging texts with the lookout ranger stationed on Sand Mountain. “Looks like the Bull is going to get it,” he wrote.

The Gold Butte Lookout was wrapped in fire-resistant material during the Bull Complex Fire.

US Forest Service

Swan Song Lost

Allen’s father and the lookout had grown old together. When Allen Jr. first saw the Bull of the Woods Lookout, they were both teenagers: he was 18 years old; the lookout was 17 years old. Now, Allen Jr. was 80 years old, and the tower, 79. They were both a little more frail.

This summer, Allen Jr. had been finding it harder to make the long uphill hikes to lookout peaks and perform the physically-demanding construction labor. If his days restoring lookouts with his son were drawing to an end, restoring Bull of the Woods would have been his perfect swan song.

On the evening of Sept. 2, Allen and his father watched a bank of smoke rising from the flank of Mount Hood. Having both been trained as lookouts and in fire science, they knew how to read the smoke and what the wind direction meant for the fate of the lookout tower. They didn’t need to say a word, and watched the smoke in silence.

The Bull Fire Complex moves close to the Bull of the Woods Lookout Tower.

US Forest Service

The last lookouts standing

Mt. Hood National Forest once had more than 80 lookout towers. With the loss of the Bull of the Woods Lookout, six remain.

“I’m feeling guilty,” Allen said. “Because people look to me to help save these last places. And I keep asking myself if I did enough or what else could I have done.”

He is devastated by the loss, but not deterred. After all, when the Sand Mountain Lookout burned to the ground, from the ashes rose the Sand Mountain Society.

The transplanted and restored lookout tower on Sand Mountain is considered a historic restoration tour de force. It is staffed by the Forest Service as well as a rotation of Sand Mountain Society volunteers, including Allen Jr.

“It’s unlikely to get permission from the Forest Service to rebuild Bull of the Woods,” Allen said. “But I’m kind of a dreamer. And if they do give us the ok, we’ve got the tools and volunteers ready to bring it back.”

The Bull of the Woods Lookout was one of the oldest and most iconic fire lookout towers in Oregon.

US Forest Service